Ohio’s Medicaid expansion: How to win when we lose

Jul 15, 2016$1.136 billion: That’s the budget gap that Ohio policymakers must face in the upcoming state budget cycle. This fiscal train wreck is no surprise—in fact, The Buckeye Institute warned policymakers in 2013 that such deficits were bound to happen. Soon, Ohio taxpayers will be on the hook for higher taxes, receive fewer public services, and suffer from less infrastructure.

Background

In February 2013, the Health Policy Institute of Ohio, The Ohio State University, the Urban Institute, and Regional Economic Models, Inc., issued an influential joint report (hereinafter “Health Policy report”) arguing that Medicaid expansion would actually help Ohio’s budget. Most of the Health Policy Institute’s imagined budget benefits relied on a tax scheme that allows Ohio to foist a portion of its Medicaid costs onto the federal government while lowering its own expenses and keeping the tax revenues for itself.

Not surprisingly, once aware that states might try such a scheme, the federal government criticized the practice and determined it to be illegal under federal law. A Buckeye Institute report alerted Ohio policymakers that the federal government was on to its fiscal shell game and that most of the so-called financial benefits of Medicaid expansion would likely disappear.

In our view, expanding Medicaid was always a bad idea for Ohio, but without any of these supposed financial “benefits,” joining the expansion has proven even more foolhardy. Unfortunately, Governor Kasich ignored our warning, successfully maneuvered around the General Assembly—which had opposed Medicaid expansion—and used the Controlling Board to sign Ohio up for the budget-busting program.

The “shell game” used to fleece Washington

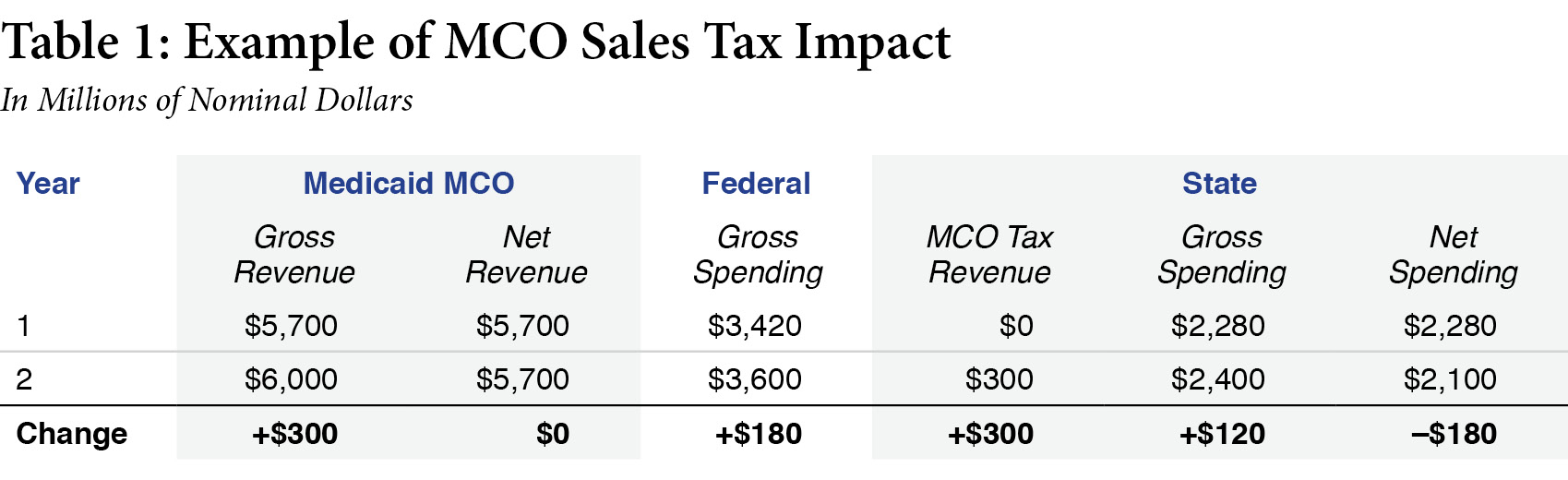

Ohio’s fiscal trick worked like this: Ohio pays per-member per-month or “capitated” premiums to private insurance firms called Managed Care Organizations (MCOs) that coordinate healthcare for Medicaid recipients. By increasing the capitated premium and subjecting that premium to the state sales tax, Ohio artificially inflates spending and thus boosts federal matching dollars. Consider the following hypothetical example:

In year one, Ohio determines that MCOs need a $475 capitated premium and there are one million Medicaid recipients. Total Medicaid managed care spending equals $5.7 billion per year, with $2.28 billion coming from the state’s coffers and—at a 60 percent matching rate—$3.42 billion from the federal government.

In year two, Ohio raises the premium to $500 and assesses a 5 percent state sales tax—the proceeds of which it will keep. Total Medicaid spending now becomes $6 billion per year, with $2.4 billion coming from the state and $3.6 billion from federal matching grants. The state spends $120 million more out of pocket on Medicaid but receives $300 million in new revenue from the sales tax. In effect, Ohio fleeces the federal government for an annual $180 million bonus, and the MCOs still get the money they need.

Governments, of course, do not like to be fleeced. Federal regulators quickly thwarted Ohio’s sales tax scheme and now consider it illegal.

Medicaid expansion will bleed out

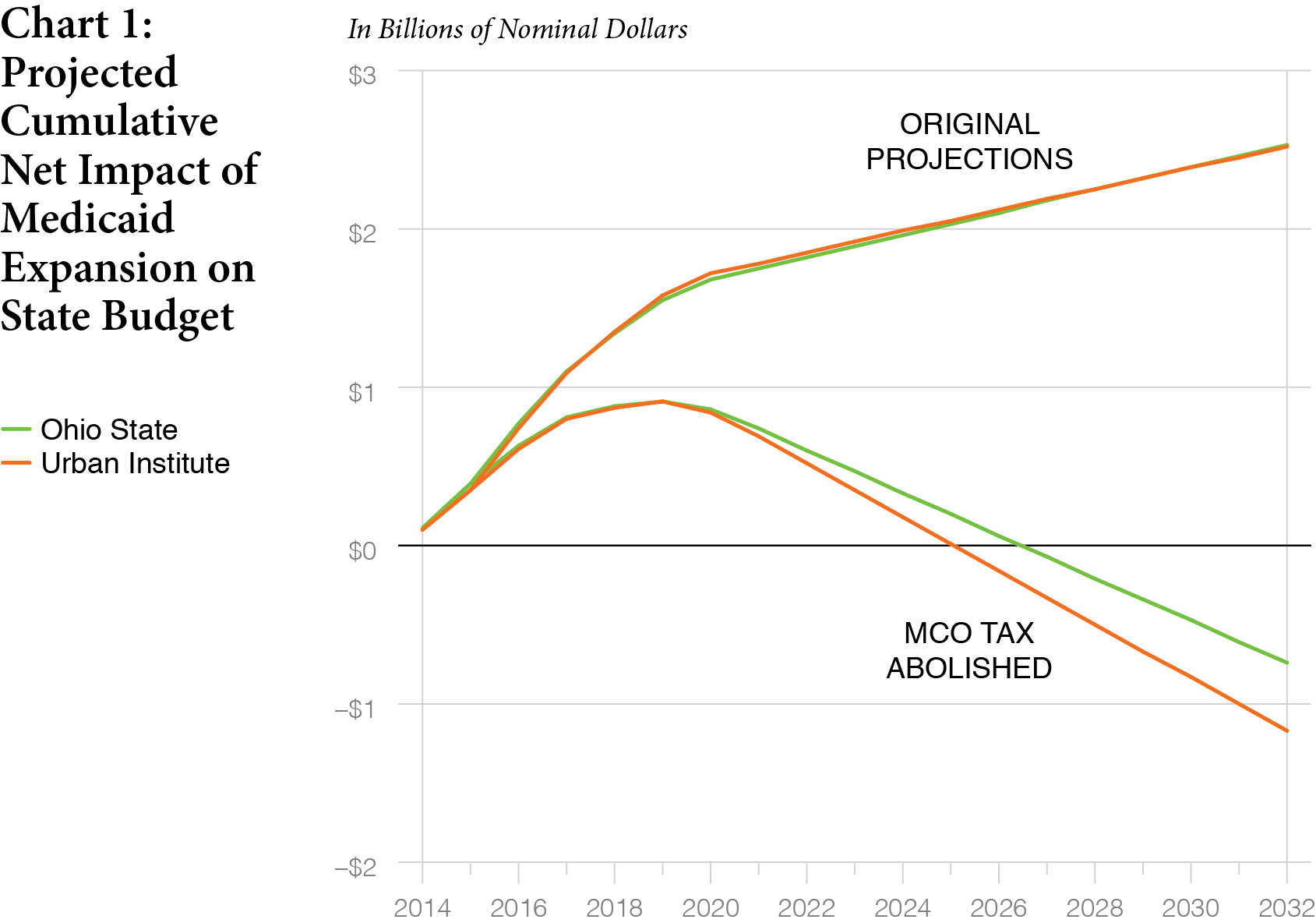

The Health Policy Institute and its co-authors had estimated that Medicaid expansion would yield net gains to Ohio’s budget. These gains, they wrongly predicted, would (depending on the economic model) range from $1.82 billion to $1.85 billion by 2022.

Unfortunately, between one-quarter and one-third of the Health Policy report’s projected financial gains flowed from the now-illicit MCO tax revenues. The Buckeye Institute analyzed how the Health Policy Institute’s estimates would change if the MCO tax became ineligible beginning in fiscal year 2016 (July 1, 2016 to June 30, 2017). Without these crucial revenues, Ohio would likely lose $1.2-$1.3 billion in anticipated funding from 2016 to 2022—even using the Health Policy report’s own estimates. If the trends continue, we fear that any fiscal gains from Medicaid expansion will be lost by FY 2026 and the program will continue to hemorrhage money for the foreseeable future.

The problem goes beyond Medicaid expansion

Ohio used its “spend-then-tax” scheme before expanding Medicaid, but the expansion has made the coming loss of these now-illicit tax revenues much worse for two reasons:

First, as predicted, expanding Medicaid added people to Medicaid’s rolls, making the sheer magnitude of the tax revenue losses larger. The Health Policy report estimated that 498,000 to 609,000 newly eligible Ohioans would enroll in the expansion program by FY 2016, bringing Columbus $131-$139 million for FY 2016. Once again the Health Policy estimates were wrong, as more than 632,000 people were enrolled in the Medicaid expansion population by the end of FY 2016.

The additional 632,000 Medicaid recipients means that Ohio currently reaps even more illicit gains under its sales tax scheme—and will therefore suffer even deeper losses next year when the scheme expires.

Second, Ohio depends on this tax scheme even more to fund the expansion population than it does to fund the pre-expansion Medicaid population. The state pays for Medicaid but Washington reimburses Ohio for a certain percentage of its expenses. The reimbursement rate varies by program. The pre-expansion Medicaid program enjoys a 63% reimbursement rate, for example, while the expansion program receives a 100% federal reimbursement until 2017. Beginning in 2017, however, that rate will slowly decline to 90% reimbursement in 2020.

The higher federal match for the expansion population means that the state yields far more illicit (and soon to expire) MCO tax revenues per Medicaid expansion enrollee than per traditional Medicaid enrollee. At the 95% FMAP that Ohio receives in 2017, the state would take in $1.15 in illicit tax revenues for every dollar it spends on the expansion population. But for the traditional, pre-expansion population, reimbursed at a 63% rate, the state only gets 15 cents in MCO tax revenues for every dollar that it spends. Thus, Ohio relies much more on its underhanded tax scheme to fund Medicaid expansion than it does to fund traditional Medicaid.

Taking revenues from the expansion and pre-expansion Medicaid populations, the state expected to gain $558 million from the sales tax in FY 2018 and $578 million in FY 2019—for a total biennial gain of more than $1.1 billion. That expectation has been dashed, leaving more than a billion-dollar hole in the state’s future budget. Filling that hole by FY 2019 will not be easy.

What we can do

Even these dark fiscal clouds come with a silver lining: The looming budget shortfall gives Ohio policymakers a real opportunity to fundamentally reform Medicaid. The federal government sets stringent rules for how states spend Medicaid dollars, and what kinds of policies and reforms states can pursue to mend their Medicaid programs. Ohio should use this pending fiscal crisis to convince Washington that the state needs more flexibility to develop innovative new plans for Medicaid.

Other states that implemented this tax-and-fleece scheme have, or have considered, hiking state taxes on all health insurance premiums (not just Medicaid premiums) in order to cover the lost revenues. But driving up health insurance costs with a broad new tax would only hurt taxpayers more. Instead, lawmakers should embrace other state-level health care reforms that will reduce costs and improve quality, such as expanding telemedicine, charity care, and licensing reform.

Conclusion

We warned Ohio policymakers not to rely on an illicit tax scheme to keep the Medicaid program solvent. Expanding Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act only made this risky decision even riskier. Unfortunately, some state leaders ignored our warnings. But all is not yet lost. We now have an opportunity for Ohio’s leadership to negotiate with Washington to structurally reform the state’s Medicaid program with new policies that would expand innovation and competition.