The Power Players Behind Supreme Court Petitions: Who’s Filing Amicus Briefs—and Who’s Winning

Feb 17, 2025This article was first published by Adam Feldman on Legalytics.

One of the first papers I read in graduate school was Caldeira and Wright’s (1988) article Organized Interests and Agenda Setting in the Supreme Court [paywall link] where the authors found, “Not only does one brief in favor of certiorari [the Court granting merits review of a case] significantly improve the chances of a case being accepted, but two, three, and four briefs improve the chances even more. This finding holds even after we (statistically) take into account other important forces in the certiorari process, such as whether conflict existed in the lower courts.” The findings have been reconfirmed and extended by many scholars since then (for example). In a more recent paper though, based on data for the terms OT 1968, 1982, 1990, and 2007, Caldeira, Wright, and Zorn found, “At the same time that the number of amicus filings on certiorari have grown – and perhaps owing to it – the influence of those briefs has steadily declined.”

This article looks at the 7,585 petitions for cert for starting at the end of the 2022 Term (June 30, 2023) and moving through the most recent petitions. 1,312 petitions are yet to be decided so 6,273 petitions from this set were already resolved. Within this group of 5,878 petitions were denied, 335 were granted, and 60 were GVRed (granted, vacated and remanded generally meaning the decisions were vacated based on a merits decision in another case that then becomes controlling on the issue).

How much impact did cert stage amicus briefs, friend of the court briefs that almost always argue for the Court to review a case decided by a court below, have on the Court’s selection of merits cases? How frequently are these briefs filed? Who is filing them? Who is most successful in determining when to file these briefs? These questions are all examined below with the most recent cert petition data.

Lay of the Land

Of the full set of 6,273 petitions 6.3% were either granted or GVRed meaning 93.7% were denied. Cert petitions can either be paid, or IFP (in forma pauperis) which means the Court fees are waived for indigents which are often filed from prison. IFP petitions, which are often handwritten from prison cells are much more frequently denied than paid petitions. In this set of 3,785 IFP petitions and 2,488 paid petitions, 98.78% of IFP petitions were denied while 85.97% of paid petitions were denied.

12 IFP and 155 paid and decided petitions had exactly one cert stage amicus brief. Three of the 12 or 25% of the IFP petitions were granted. The total number of these petitions with an amicus brief is too low to provide much of a sense of this relationship. 13.55% of the 155 paid petitions were granted which is actually a bit lower than the total rate of grants for paid petitions.

13 IFP petitions had more than one cert stage amicus brief attached of which 3 (23%) were granted. 273 paid petitions (32.4%) of the 841 total with more than one cert stage amicus brief were granted showing a strong correlation between grants and paid petitions with more than one cert stage amicus brief. This number is still well below 50% though.

When combined, 24% of IFP petitions and 29.5% of paid petitions with at least one amicus brief were granted across the entire set. 361 of the 1,312 outstanding petitions have at least one associated cert stage amicus brief.

* Note: The data are based on Supreme Court docket entries which unfortunately means that some groups are missed in the analysis if they are listed as part of “et al.” on the docket.

Specific Findings

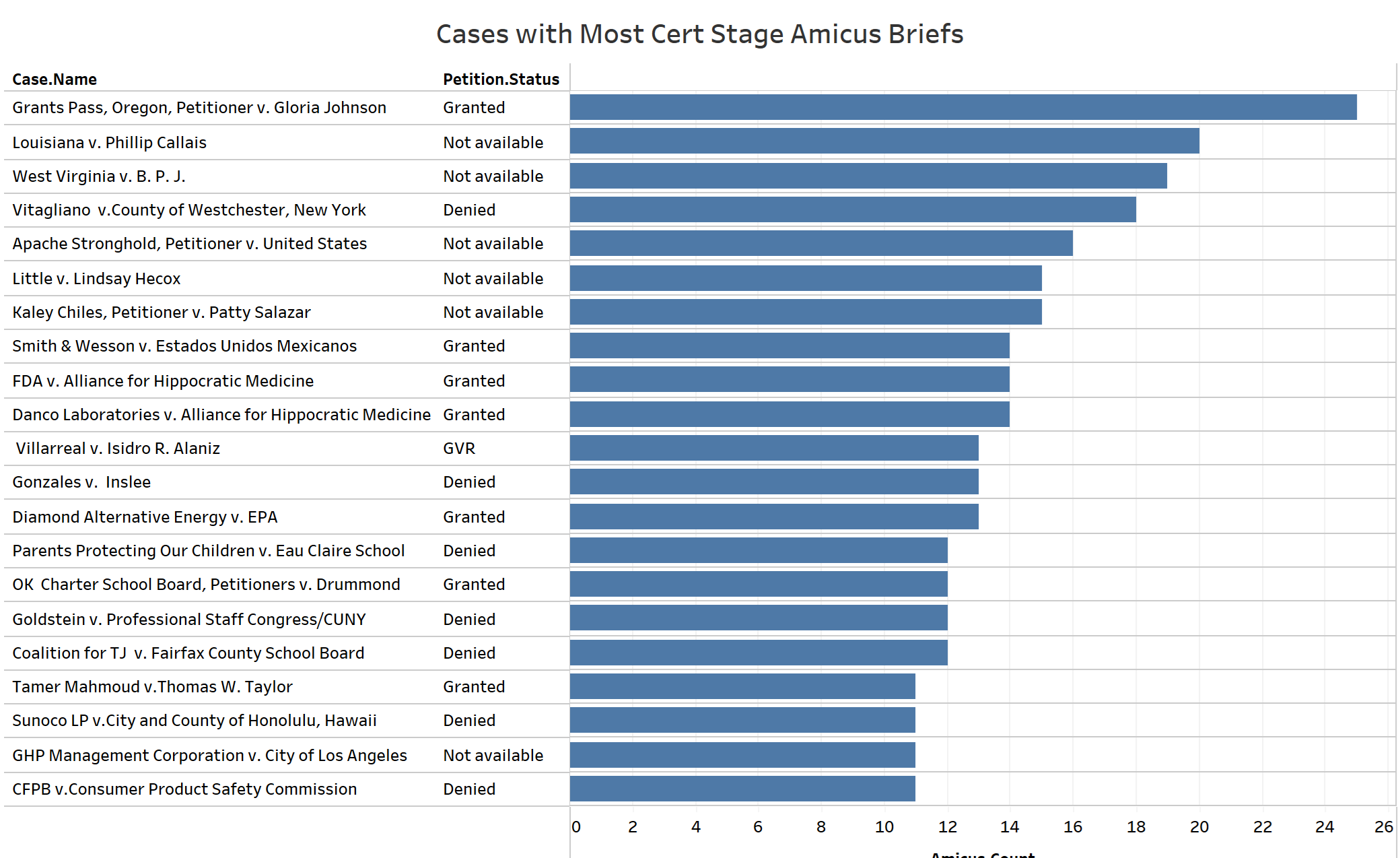

This section focuses on the players filing cert stage amicus briefs and the cases where these briefs were already filed. Starting with the cases with the most cert stage amicus briefs we see:

Five of the seven petitions with the most cert stage amicus briefs are still undecided. Grants Pass had the most cert stage amicus briefs in this set with 24. The decided petition with the second most cert stage amicus briefs, Vitagliano v. County of Westchester, was denied. In total, six of the 21 petitions in the cases above have yet to be decided, seven were denied, and eight or 53.3% were either granted or GVRed.

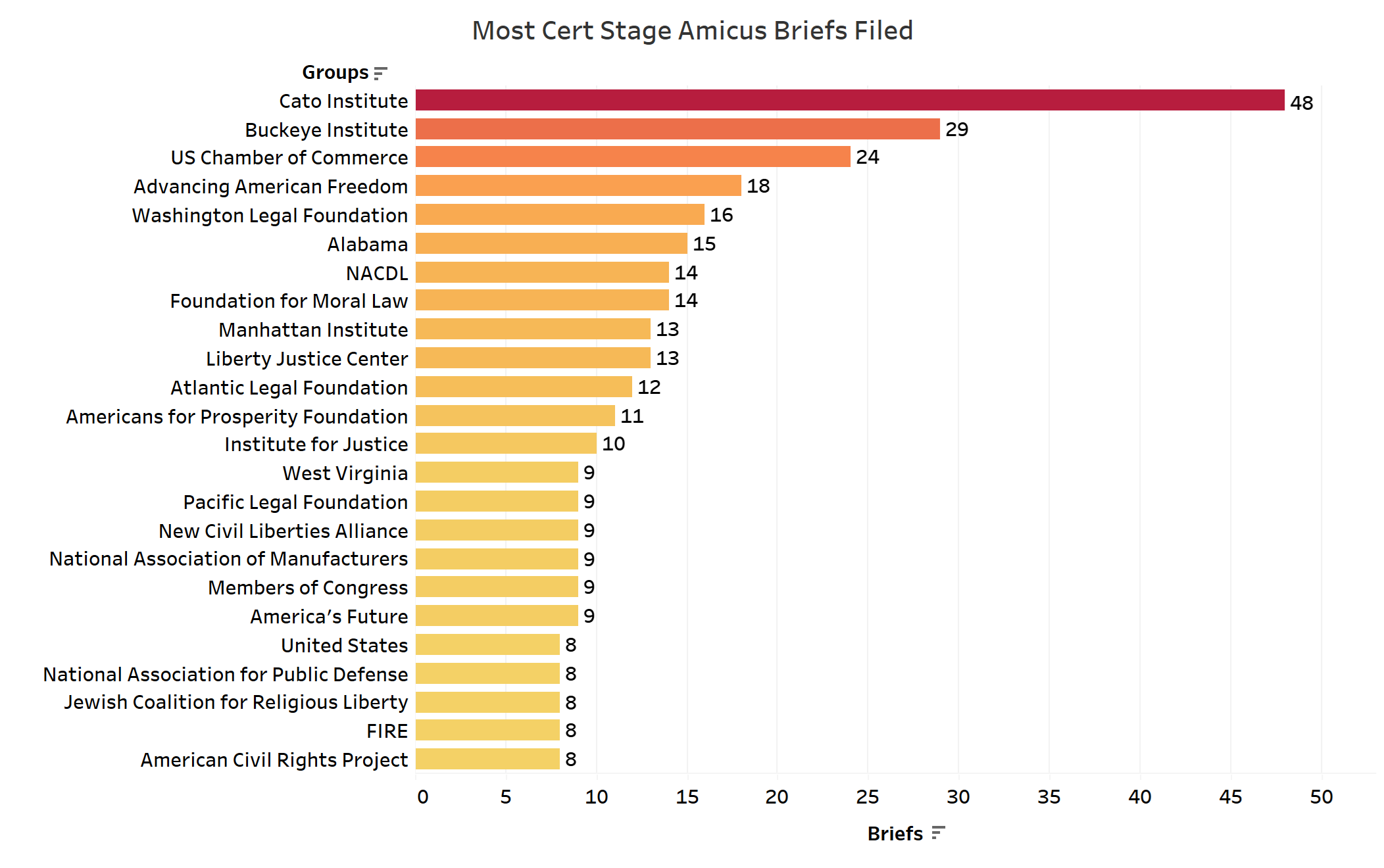

To begin looking at amicus filers, the next graph has those with the most filings during this period.

The Cato Institute filed the most briefs with 65% (19) more filings than the Buckeye Institute which filed next most briefs. Along with the Buckeye Institute the US Chamber of Commerce, Advancing American Freedom, and the Washington Legal Foundation were the groups which filed the most briefs.

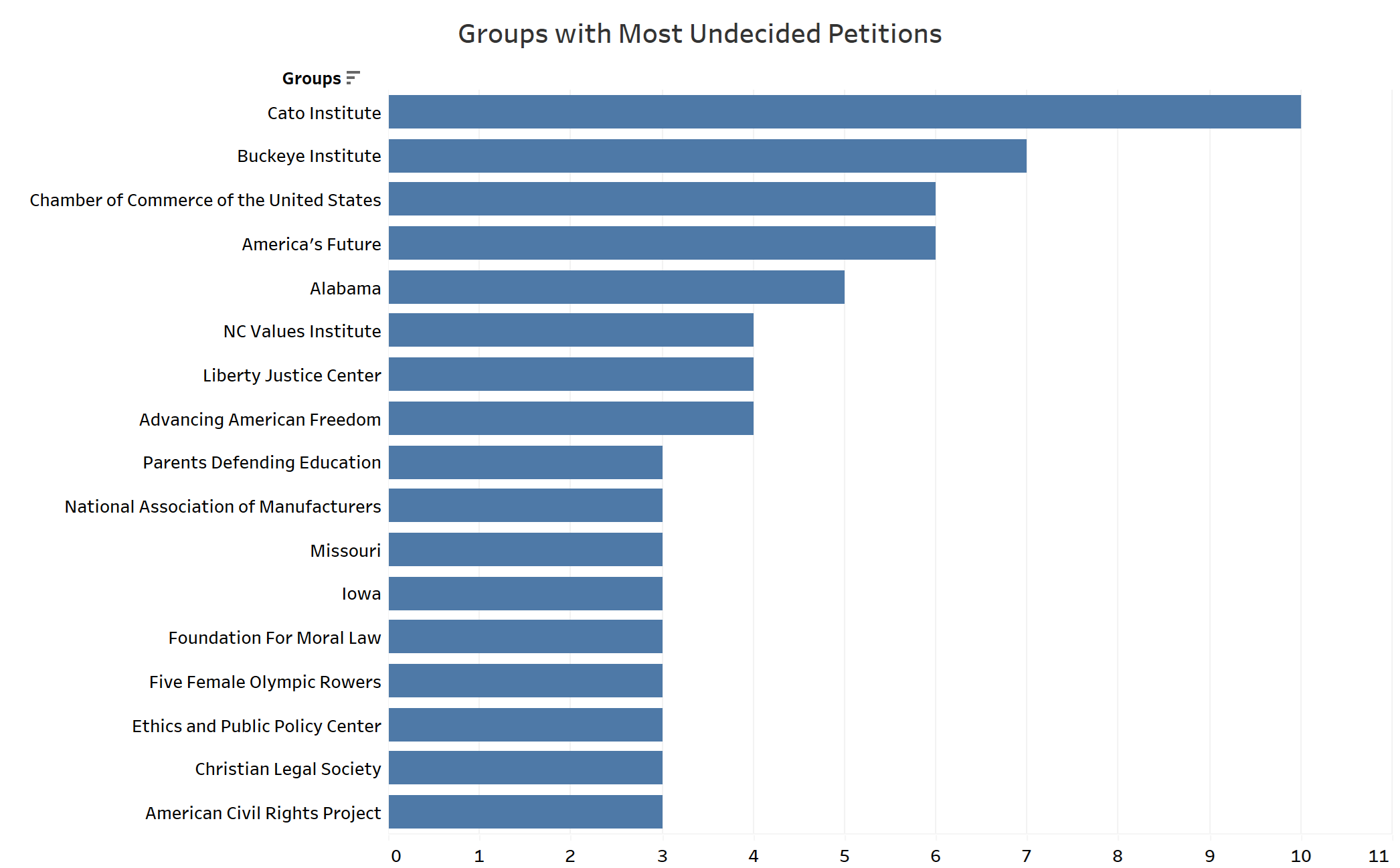

Looking at groups that filed cert stage amicus briefs in cases with the most undecided petitions we see the following.

While there are similarities at the top of this graph and the one prior, America’s Future has a higher level of filings on this chart along with North Carolina Values Institute and Parents Defending Education.

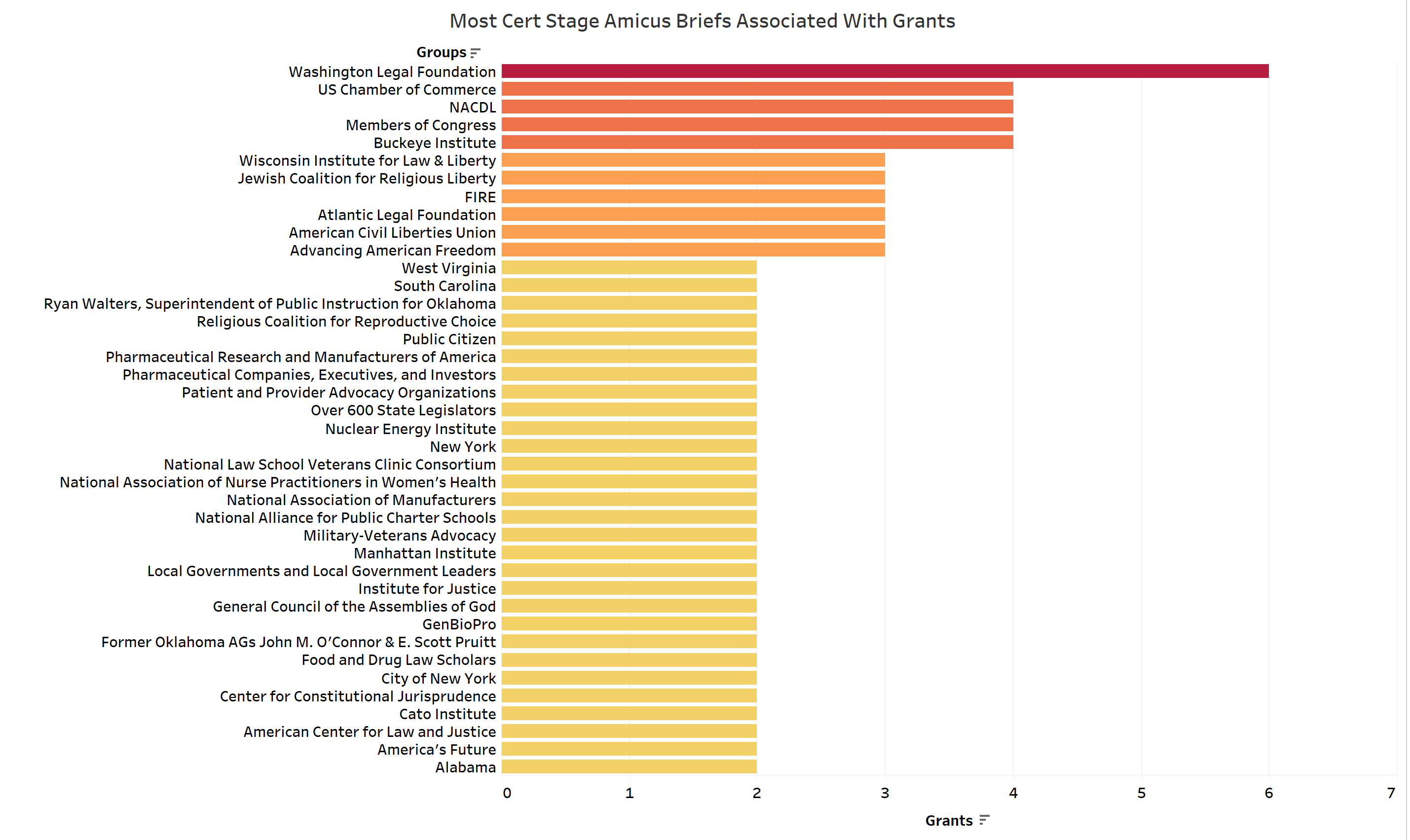

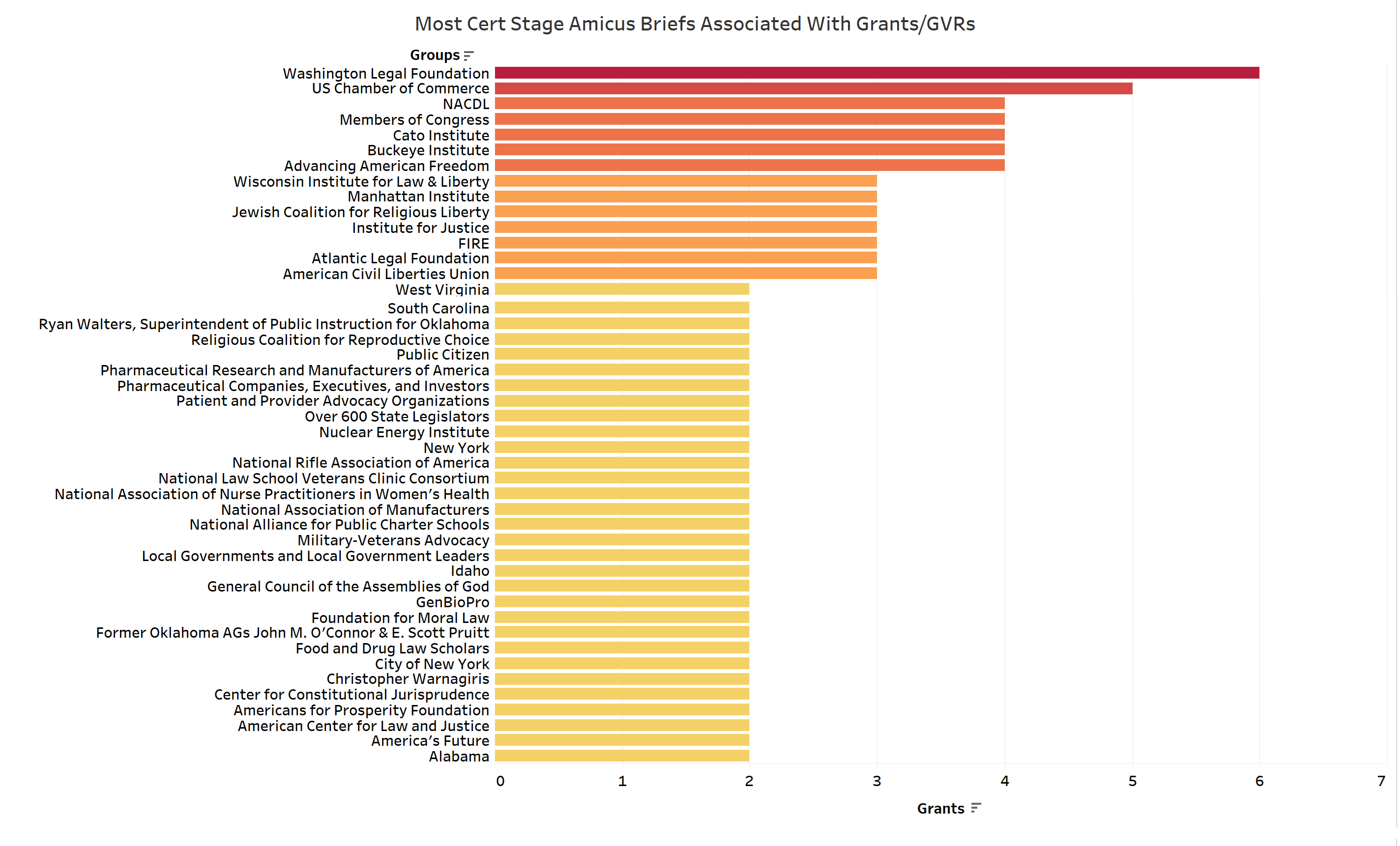

Now a look at successful cert stage amicus filings associated with granted petitions. The next graph covers groups with the most associated grants during this period. This graph does not include GVR decisions.

The Washington Legal Foundation has the most associated grants with two more than the next set of groups that include frequent filers US Chamber of Commerce, the National Association of Defense Lawyers (NACDL) and the Buckeye Institute. Members of Congress were also at this level although this generic title could belong to different members of Congress. Other highly successful repeat filers include the Wisconsin Institute for Law & Liberty, FIRE (Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression), Atlantic Legal Foundation, and the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU). The groups in this graph all filed in multiple granted cases.

Adding in GVRs changes the graph a bit.

Here the US Chamber climbs by one grant and the Cato Institute moves up two spots to the second tier of groups based on grants. Repeat cert amicus filer Institute for Justice rises in the chart when GVRs are also factored in.

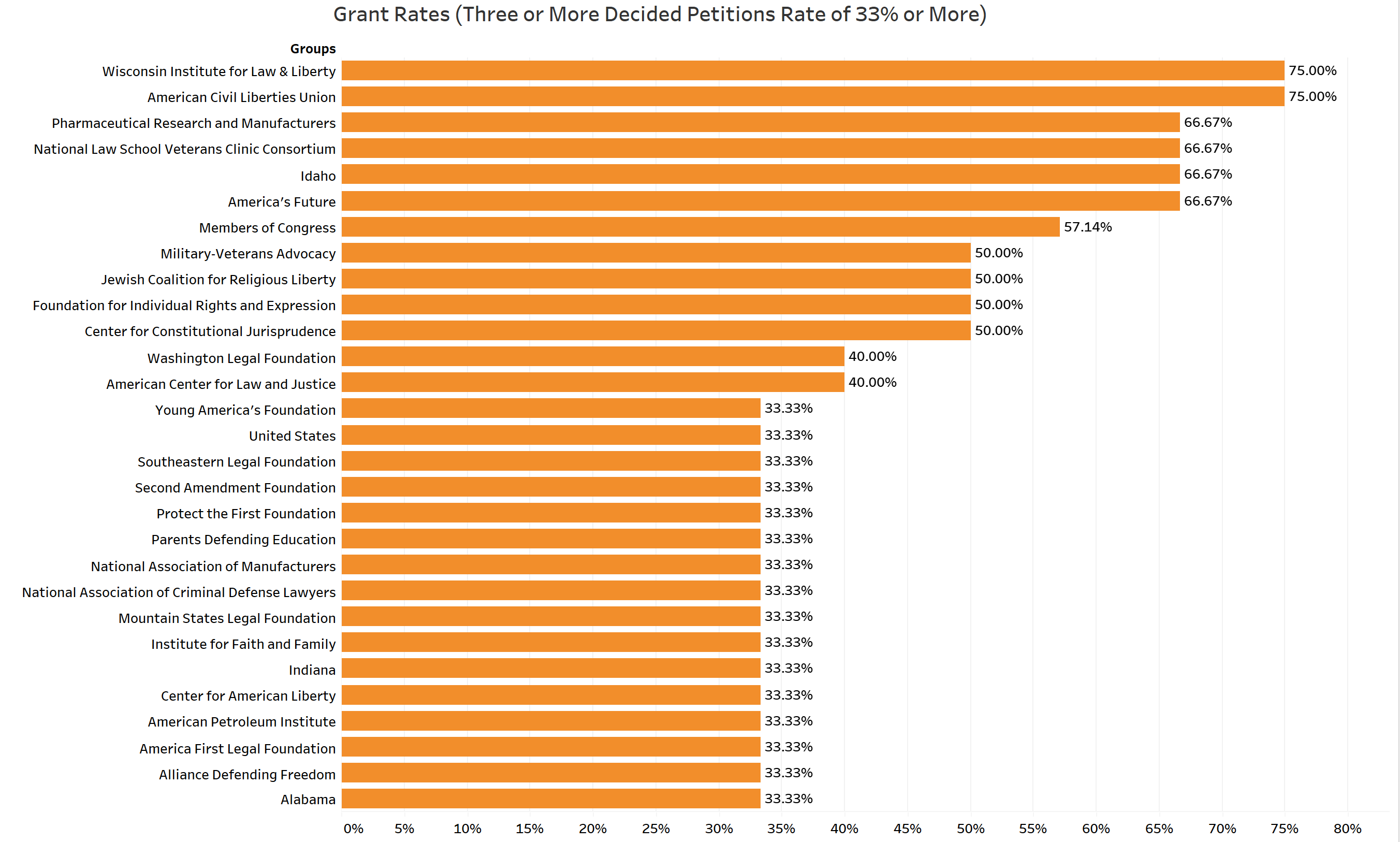

Now a look at groups that filed cert stage amicus briefs most efficiently, defined by non-denied petitions (either grants or GVRs).

The groups with the highest grant rate at 75% are the Wisconsin Institute of Law & Liberty and ACLU. Both had grants on three of four petitions. The next set of groups including all had grants in two of three cases where they filed cert stage amicus briefs. Also, notably the Washington Legal Foundations 40% grant rate comes in the form of six grants from 15 briefs and National Association of Manufacturers 33.33% comes from four grants in 12 cases.

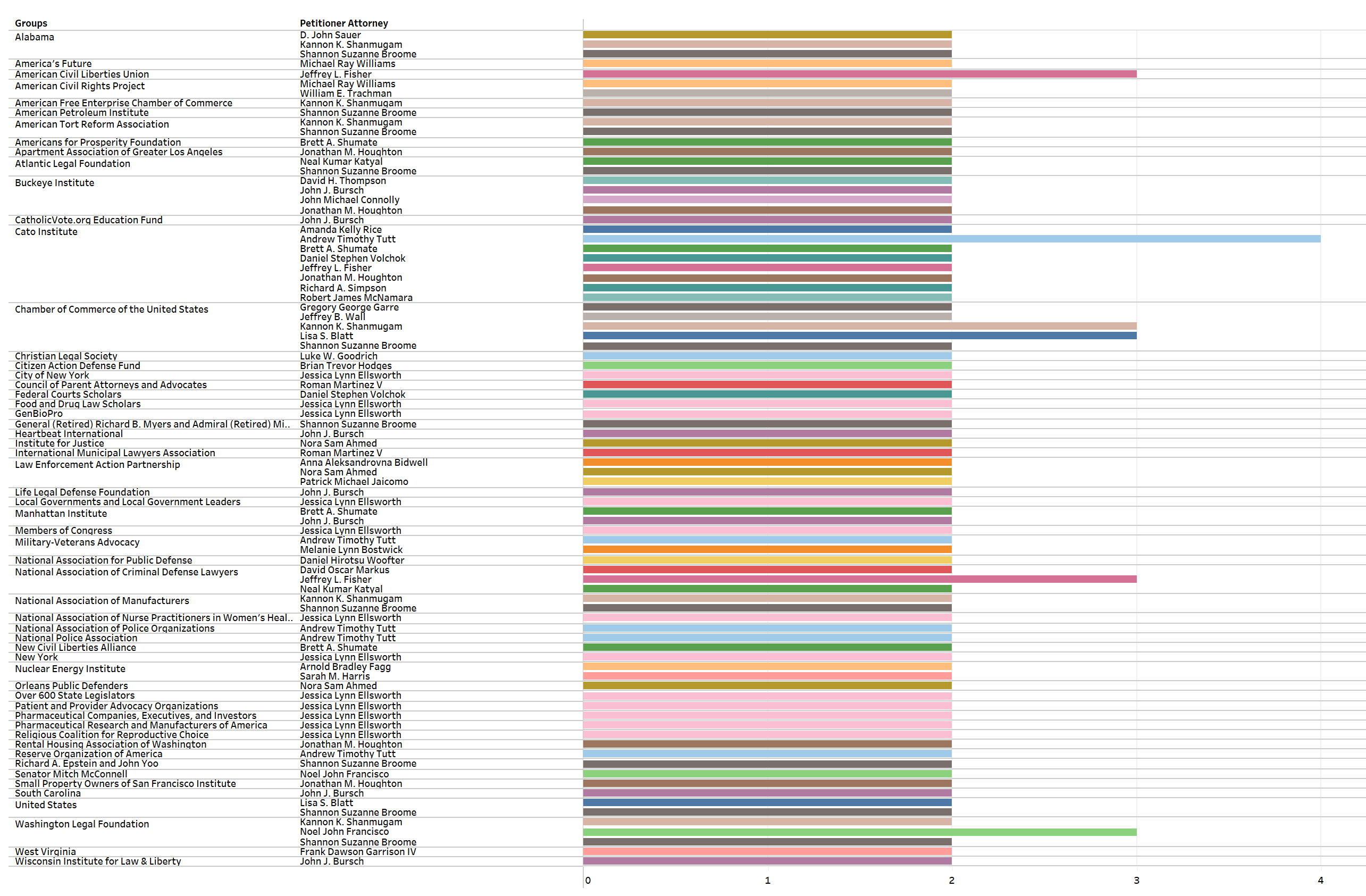

The next graph associates the amicus filers with the merits attorneys on the petitions. The focus is on groups with multiple briefs associated with petitions filed by specific attorneys.

Certain counsels of record on the petitions have multiple petitions associated with specific amicus filers. The Chamber of Commerce filed briefs in multiple cases with petitions from several top including Kannon Shanmugam, Lisa Blatt, Gregory Garre, Jeffrey Wall, and Shannon Broome. The Chamber was the only group that filed three or more amicus briefs in cases with petitions from two different counsels of record (Kannon Shanmugam and Lisa Blatt).

Looking at the other groups with the filing the most briefs associated with specific attorneys we find that the ACLU and the National Associated of Criminal Defense Lawyers both filed three briefs in cases with petitions from Stanford Supreme Court Litigation Clinic and O’Melveny & Myers attorney Jeffrey Fisher and the Washington Legal Foundation filed three briefs in cases with petitions from previous Solicitor General Noel Francisco. The Cato Institute is the only group to file more than three briefs (four) in cases with petitions with the same counsel of record, in this instance with Arnold & Porter’s Andrew Tutt.

Conclusion

The findings in this article reinforce and update previous scholarship on the role of cert stage amicus briefs while also highlighting notable shifts in their impact over time. While the presence of multiple amicus briefs continues to correlate with a higher likelihood of a grant, the overall success rate remains well below 50%, suggesting that while amici can be influential, they are not determinative. The data also provide valuable insights into the key players filing these briefs, their success rates, and their alignment with specific merits attorneys. Notably, certain organizations—such as the Washington Legal Foundation, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, and the ACLU—demonstrated high efficiency in supporting granted petitions, though further research is needed to understand the strategic factors driving their success. Other studies could (and some are already beginning to) explore the evolving influence of amicus briefs in light of increasing filings, shifting ideological trends on the Court, and variations in judicial receptiveness to different amici over time. Additionally, examining the interplay between cert stage and merits stage amicus participation could provide a more holistic view of how these briefs shape Supreme Court litigation from start to finish.